07 Mar Kate Walker, hero of Robbins Reef

Everyone who sails New York Harbor is familiar with Robbins Reef. Since 1883, this squat little white and brown lighthouse has stood on a rocky reef in the Upper Bay, about a mile north of Staten Island. As lighthouses go, it’s not particularly pretty. But it has a fascinating history, starring a tiny but determined woman who defied the norms of her time and became an unsung hero of the harbor.

To this day, ship captains and harbor pilots still refer to Robbins Reef as Kate’s Light, in honor of the remarkable woman who tended the light for 33 years. Kate Walker didn’t set out to be a lighthouse keeper, or plan to spend her life on a tiny rock islet in New York Harbor. But fate had other ideas.

Robbins Reef light today, with New York City in the background. Photo: Wall Street Journal

A new life in America

Katherine Gortler was born in Germany in the 1840’s. Widowed at a young age, she emigrated to America with her 7 year old son in search of a new life. While waitressing at a boarding house in Sandy Hook, NJ she met Captain John Walker, a retired sea captain and assistant keeper of Sandy Hook Light. He offered to give her English lessons. A romance soon blossomed; Kate and John were married and settled into a home on the grounds of the Sandy Hook Lighthouse.

Robbins Reef circa 1918. Note the ladder and rowboat on davits. Photo: USCG

Shortly after they wed, Captain Walker accepted a position at Robbins Reef, which had recently been rebuilt as one of the most modern lighthouses on the East Coast. Unlike Sandy Hook Light, which was on land and afforded the family a garden, the Robbins Reef Light was a mile out in the harbor, accessible only by boat.

There was no dock at the Robbins Reef. To get to the lighthouse, you had to climb up a steep ladder from a rowboat, then lift the boat up on davits for safe keeping. Surrounded only by rocks, seals, seagulls, and strong currents, it was a big change for the young family – especially Kate.

“When I first came to Robbins Reef, the sight of the water, whichever way I looked, made me lonesome. I refused to unpack my trunks at first, but gradually, a little at a time, I unpacked. After a while they were all unpacked and I stayed on” she later recalled.

At Robbins Reef Kate was assistant lightkeeper, while also managing all the household duties. She transformed the 5 rooms in the 20 foot wide cast iron cylinder into a comfortable family home. She was a petite woman – not even 5 feet tall and weighing just 100 pounds – but she wasn’t afraid of hard work. She rowed her children to and from school each day on Staten Island, a mile in each direction.

Mind the light, Kate

Tragedy struck just a couple of years later when John Walker fell ill and died of pneumonia. As he was being taken ashore to a hospital, his last words to his wife were “Mind the light, Kate.”

For the second time in her life, Kate was a widow and a single mother. But there was work to be done, and Kate took solace in the rituals of minding the light. She immediately took over her husband’s duties, and kept the light burning for the next 33 years.

Kate Walker filling oil lamps. Photo: Lighthouse Digest

Tending to the light at Robbins Reef was a demanding job. Each night, gunfire from nearby Governor’s Island would sound at sunset. That was Kate’s signal to set out the kerosene lamps that reflected onto a large lens and projected over the harbor, lighting the dangerous reef below. Every few hours, she refilled the lamps and wound the clockwork that drove the rotating lens.

She kept up the vigil until daybreak, when at last she would sleep until it was time to row the children to school. During the day she recorded weather and ship traffic, inventoried and requisitioned supplies, washed the lamps, trimmed the wicks, polished brass, and cleaned the Fresnel lens to prepare for the next night.

When fog rolled into the harbor, Kate fired up an engine in the lighthouse cellar that sounded a fog horn at 3 second intervals. If the engine failed, Kate had to climb to the top of the tower and ring a bell to alert the Lighthouse Depot ashore to come out and repair the equipment.

A woman’s work is never done

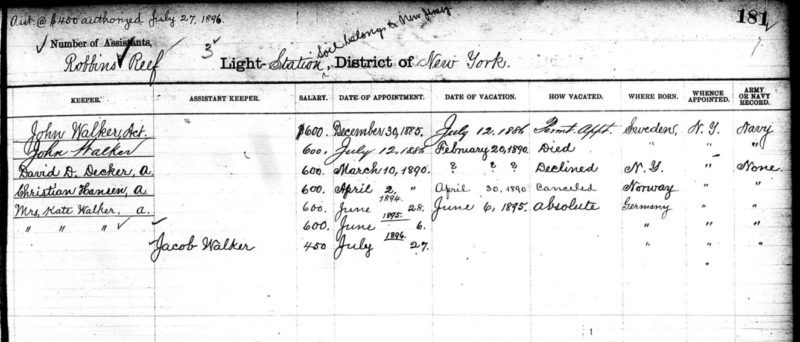

Immediately after her husband’s death, Kate applied to the Lighthouse Commission to become the official lightkeeper at Robbins Reef. Officials objected, probably doubting that a woman of such diminutive stature with two dependent children could do the demanding work. But single women in the late 1800’s had few options, and she needed the work to support her family. So she continued to petition the commission. Finally, after several men had turned down the job – and long after Kate had proven capable of doing the work – she was appointed official lightkeeper four years later.

Station assignments for Robbins Reef Light. Several men turned down the job before Kate was confirmed. Image: US Lighthouse Society

The job paid $600 per year. Once a year, a lighthouse official visited Robbins Reef to drop off a few tons of coal for the generator, barrels of oil for the lights, and an envelope containing Kate’s wages. Other than that, she was mostly on her own.

Despite her initial reservations, Kate grew to love the routine of lightkeeping and the isolation of living at Robbins Reef. She took satisfaction in doing important work, and trained her son Jacob to be her assistant. She rarely left Robbins Reef except to row her children to school and pick up supplies. In 1909 she told the New York Times, “Someone could offer me a millionaire’s mansion and I’d feel like I was in prison.”

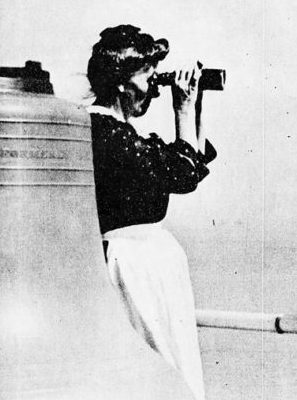

Kate Walker, circa 1909. Photo: USCG

In addition to tending the light and raising her children, Kate aided in rescues of distressed ships in the harbor – even though it wasn’t part of her official duties. It was dangerous work, but despite her small size she was strong and had become an expert rower. By her own count, she saved 50 lives in the treacherous waters around Robbins Reef, including many fishermen whose boats were blown onto the reef during storms. She herself suffered several close calls when storms whipped up the harbor as she was rowing back from Staten Island.

Kate kept the light at Robbins Reef until 1919, when a new government regulation mandated her retirement at age 71. She reluctantly moved to Staten Island, where she could still keep an eye on the lighthouse.

Katherine White died in 1931. Upon her death, the New York Evening Post wrote this in her obituary: “A great city’s water front is rich in romance… There are queenly liners, the grim battle craft, the countless carriers of commerce that pass in endless procession. And amid all this and in the sight of the city of towers and the torch of liberty lived this sturdy little woman, proud of her work and content in it, keeping her lamp alight and her windows clean, so that New York Harbor might be safe for ships that pass in the night.”

Katherine Walker kept the promise she made to her dying husband, tending the light at Robbins Reef for over three decades. In doing so, she became a true hero of New York Harbor and an inspiration for women everywhere.

Kate’s legacy

I’ve sailed by Robbins Reef hundreds of times, and each time I offer up a little prayer of thanks to Kate for keeping the harbor safe. I often wonder if the thousands of people that pass by Robbins Reef each day on the Staten Island Ferry know Kate’s story.

USCGC Katherine Walker. Image: USCG

The U.S. Coast Guard honored her in 1996 when it commissioned the USCGC Katherine Walker. The 175’ Keeper Class buoy tender maintains 335 aids to navigation in New York Harbor, New Jersey, and the Long Island Sound – a fitting tribute to Kate’s legacy.

Soon, even more people will know her name. Just this week, the City of New York announced that it will erect a statue of Katherine Walker at the Ferry Landing on Staten Island. The monument will honor this small but mighty woman, a hero who worked tirelessly to ensure safe passage for all sailors in the harbor.

In honor of International Women’s Day we’re proud to share this story of an incredible woman in New York and maritime history. If you liked this story, check out this article about great women sailors who’ve inspired us: Women Sailors Rock!

You can read more maritime history here: JFK, the sailing President and A Shamrock for St. Patrick’s Day